Follow us on social media!

Welcome back to Diaries from Analog Mars! If you missed Jin’s first entries, you can find them here.

In part 4, Jin gets acquainted with his EVA suit, learns the value of good food in the confines of space, maintains the habitat, and begins to observe the unique social dynamics and bonding of a space analog environment.

It was Sol 1 – our first day on Mars, ‘in-sim’.

Being ‘in-sim’ meant that we had to begin living as if we were really on Mars. This meant that the atmosphere outside had become unbreathable and the only way we were leaving the Hab was in spacesuits. If we needed help with planning and operations, we needed to go through Mission Support and pass our questions through CapCom when the communications window opened at 7 PM MDT. Being ‘in-sim’ also meant that we could no longer leave the engineering airlock open for ventilation. It had to remain firmly closed unless someone needed to use the tunnels to get to the other buildings. I applied a 40-minute delay in responding to personal emails, which was redundant because I was too busy to respond to them immediately anyway.

We started the day with breakfast pancakes made by Dave: a mixture of pancake mix and whole-wheat flour, doused in syrup and garnished generously with reconstituted blueberries. The occasional handful of peanuts was our protein. For the first time since we had arrived at the facility, we ate our fill and were stuffed. We would need it for the day ahead.

After breakfast, I conducted the first health check as part of my duties as Health and Safety Officer. I checked the blood pressure, pulse, blood oxygenation, and general status of all the crew. Then, we began our morning planning meeting.

Dr. Rupert had requested the previous day that we leave our orange bucket in the engineering airlock so that she could pick it up later. However, we also needed this orange bucket to clean the Hab and the engineering module, our primary task for the day. The words ‘the orange bucket’ began to crop up so frequently in our conversations, that it became our first inside joke while in-sim. Inserting “the orange bucket” into a sentence dependably elicited a giggle. I swear, it’s funnier than it sounds!

While Lindsay and Inga got to work cleaning the Hab’s lower deck, Dave took the upper deck and I went over to the RAM. The floors were covered in loose peach-colored Martian dust, and more had caked into the steel floor as dried mud. Dave asked if cleaning was what I had been expecting to do on Mars; I replied, “No, but I should’ve!” On Mars, the interior of the spacecraft would definitely need to be kept clean. Martian dust is fine stuff. I can be inhaled, find its way into bedding and food, or even cause equipment issues. On the Moon, where the dust is composed of microscopic, jagged shards, cleanliness could become a life-or-death issue.

I returned from mopping the RAM to find Lindsay and Inga going over every square inch of the Hab’s lower deck floor with paper towels. Eventually, it sparkled with cleanliness – although we don’t know how long this will last, because we are surrounded by literal mountains of dust! We decided that our boots would be kept in the airlocks to slow the inevitable tide of dust. Space analog simulations (or at least the MDRS) are the furthest thing possible from the common put-down of ‘Space Camp for adults’; while they are a lot of fun, they are also a lot of hard work and labor.

(Then again, I’ve never been to Space Camp.)

After leaving The Orange Bucket (hee hee) in the engineering airlock, Lindsay put together broccoli cheddar soup, which we ate ravenously after the exertion of the morning.

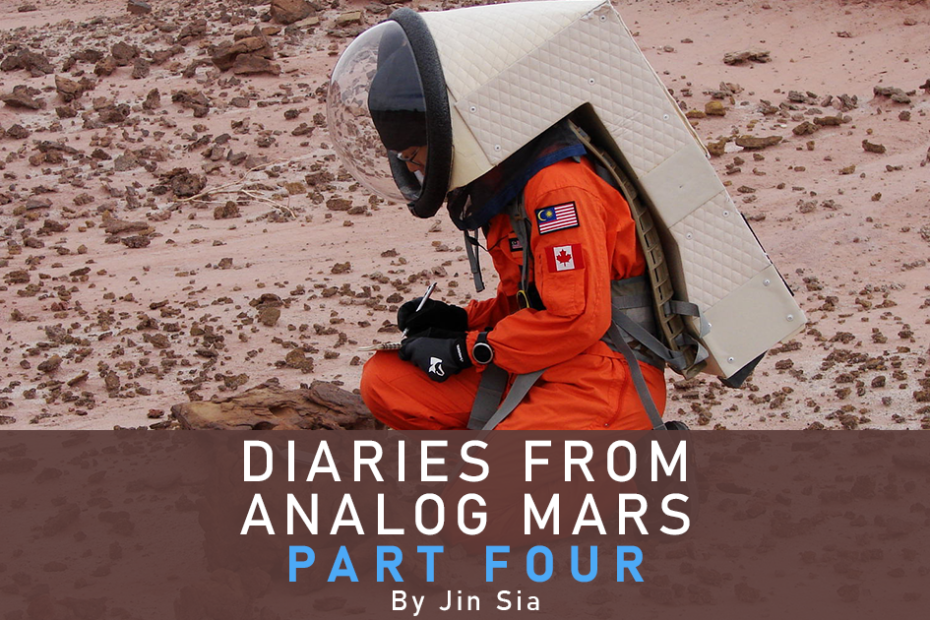

In the afternoon, we finally started our spacesuit training. We were supposed to do it the day before, while out-of-sim, but simply ran out of time. These suits, whose development is led by Scott Davis of the Mars Society NorCal, are bulky, heavy, and difficult to maneuver in. These disadvantages are by design. The future suits that humans will use to explore Mars will be far more dexterous and lighter than the spacesuits of today, but they will likely still get in the way and make fieldwork difficult.

Lindsay, being a veteran of MDRS and HI-SEAS, recommended that we practice donning and doffing, driving, and climbing hills with the suits, as doing anything in them requires some finesse. However, going outside would require filing an EVA request the day before with Mission Support. So, instead, we practiced donning and doffing the backpacks indoors, then communicating with each other via suit radio. Ensuring that they remain secure and maintain a comfortable spacing between the top of one’s head and the roof of the helmet demands a lot of attention to the straps: a careful balance between weight on the hips and weight on the shoulders.

Almost everything we do on Mars is a team activity by sheer necessity, and the suits were no exception. Simply putting on and securing the backpacks required at least one helper. The process for putting them on requires several steps, ranging from securing the radio earpiece with a headdress to climbing into the harness from underneath and hoisting it off the table. Once the backpack is on, the helmet prevents you from seeing what’s directly below you. My experience as a scuba diver became useful for securing my buckles and stowing my radio by touch.

To keep the faceplate from fogging and to ventilate the helmet, a fan in the backpack draws in outside air and blows it against the faceplate through vents on each side of the helmet. We also experimented with our radio settings for communications. It quickly became apparent why astronauts talk in such methodical, systematic ways when on EVA – communicating by radio is simply much more clunky and unreliable than having a normal conversation.

While we couldn’t go outside, we could practice our suit skills by walking through the pressurized tunnels that connected the buildings as long as we didn’t linger there. The MDRS’s Hab is connected to the tunnel network through the engineering airlock behind it on the lower deck. We exited through it and walked into the RAM and back, letting us get some practice maneuvering the backpack in tight spaces. Soon, we became pretty proficient and felt confident about heading out on real EVAs!

Not long after entering the tunnel network, we were forced back inside by rain… er, I mean, a ferocious Martian dust storm. No matter, practice was done. Suit training is one of my favorite team bonding experiences so far.

I was on dinner duty and decided to make a Malaysian staple: Chinese-style fried rice. While I boiled some white rice in a pot (with a little less water than normal to make the rice firm), I rehydrated some freeze-dried onions, carrots, string beans, and corn in a frying pan. Then, after the rice was ready, I began frying the reconstituted vegetables and added the rice. After seasoning with generous amounts of soy sauce and a touch of brown sugar (I would’ve used hoisin sauce but we didn’t have any), the upper deck of the Hab was filled with the delicious wine-like fragrance of the soy sauce mixed with the aroma of the frying onions. I served it with sides of scrambled eggs made from powder and rehydrated fried chicken.

I was worried that without my usual ingredients, the fried rice would taste bland.

Instead, it was the best fried rice I’ve ever had! It was practically indistinguishable from the fried rice served in the mamak and hawker restaurants I frequented in Kuala Lumpur, which I have not visited in over two years. This made me question: were they using freeze-dried ingredients?!

After dinner, we began journaling as part of Inga’s pilot study. She plans to run journal studies for future crews on how team members interact, and she is testing the process on us. For this pilot study, she will not be using our entries, but rather the process of making our entries – shedding light on how long it takes, whether it significantly inconveniences us, and how difficult it is to make them diligently. This was an interesting insight into how the scientific process works in the field of sociology.

The crew talked late into the night about making change in the world we live in, and in doing so, learned a little about each other.

It was a good first sol on Mars.

Be a part of this!

The Mars Society of Canada offers a professional and credible platform for all Canadian space advocates to influence public opinion and government policy. By becoming a member of our federal not-for-profit, you provide direct support to our public outreach and Mars exploration advocacy efforts. We proudly represent the voice of thousands of Canadians who believe in the profound benefit of space exploration, and a multi-planetary future for humanity.

Edited by Evan Plant-Weir